JOURNAL

Martha's Orange Almond 'Cheesecakes' for Jane Austen's Birthday Tea

Celebrate Jane Austen's Birthday with cheesecakes Jane herself enjoyed

I spent hours as a child cooking with my grandmother in the kitchen at Chawton House, baking cakes and scones for the tea room we ran from the Great Hall at the front of the house. I have lots of favourite recipes from Chawton – this one is from the cookbook of Martha Lloyd, who lived with Jane Austen in Chawton Cottage.

Knowing that Jane would have eaten them too makes Martha’s Orange Almond Cheesecakes particularly special and below is my version of the recipe. The tarts are not cheesecakes as we would know them today - there is no cheese in them at all!

Martha's Orange Almond Cheesecakes

Bake your own and join our fourth annual Jane Austen Birthday Tea LIVE on Facebook on Saturday 19th December at 3pm EST at Austen Heritage @CarolineJaneKnight. I will be joined by award winning narrator of The Complete Works of Jane Austen, Alison Larkin, to share a cup of tea and celebrate Jane’s birthday.

Stay tuned to @AustenHeritage and @AlisonLarkinPresents for tips, recipes, and announcements leading up to the event!

Martha’s Orange Almond Cheesecakes - makes 12 - 15

2 large oranges

4oz/110g/cup caster (superfine) sugar

4oz/110g ground almonds

2 whole eggs, separated, plus 2 egg whites

2oz/50g butter, melted and cooled

1lb/450g shortcrust pastry

Icing sugar for dusting

Preheat the oven to 375°F/190°C/Gas Mark 5.

Step 1: Roll and cut the pastry

1. Roll out the shortcrust pastry about 2mm thick - I prefer my the pastry quite thin, but you could make it 3mm if you prefer. Cut it into rounds to fit tartlet tins (patty pans) about 2½ inches/6.5cm across and ¾ inch/2cm deep. Line the tins with pastry, pricking the bottom of each.

Step 2: Melt and cool the butter

2. Melt the butter in a pan and pour into a bowl to cool

Step 3: Prepare the oranges

3. Cut the peel from one orange with a sharp knife, taking care to remove any white pith. Finely grate the zest (skin) from the other orange.

Step 4: Pulverise the cooked orange peel and add

4. Gently simmer the orange peel from the first orange in water until soft, drain and pulverise with some of the sugar. Put into a bowl and add the rest of the sugar, ground almonds and orange zest from the second orange. Mix well.

Step 5: Add the cooled melted butter and 2 beaten eggs

5. Once the orange almond mixture is well mixed, add the cooled melted butter and 2 beaten eggs.

Step 6: Whisk 2 eggs whites and fold into the orange almond mixture

6. Whisk 2 eggs whites in a bowl until they form soft peaks. Fold a couple of spoonfuls into the orange almond mixtures, before folding in the rest. To make light cheesecakes, it is important to gently fold the mixture to retain the air, rather than stir.

Step 7: Fill the pastry cases and bake for 20 minutes

7. Fill the pastry cases with the orange almond mixture, about 4/5 to the top (the filling needs room to expand). Bake for 20 minutes.

Step 8: Cool, dust generously with icing sugar and serve

8. Remove cheesecakes from the patty pans and cool on a wire rack, dust generously with icing sugar and serve.

You can also find a version of this recipe on page 123 of The Jane Austen Cookbook by Maggie Black and Deirdre Le Faye.

I know you will enjoy Martha's Orange Almond Cheesecakes as much as I do and look forward to sharing them with you on Jane's birthday. Don't forget to sign up for our Jane Austen Birthday Tea here.

Caroline

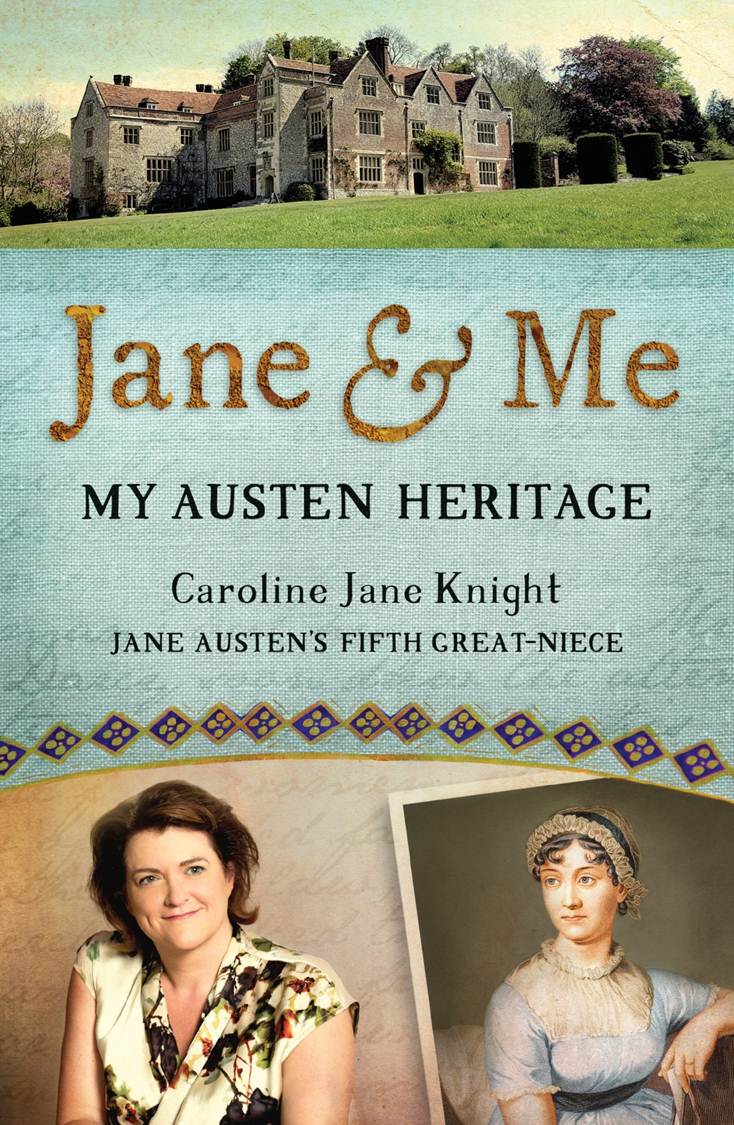

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can hear more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, narrated by Alison Larkin. AUDIOBOOK available at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SUBSCRIBE BELOW TO AUSTEN HERITAGE

Austen Knight family fun in the snow

JANE AUSTEN's fifth great niece shares her childhood memories of the Chawton estate in the snow.

As the Chawton estate is covered in snow, Caroline Jane Knight, Jane Austen’s fifth great niece and the last Austen descendent to grow up on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote, remembers the excitement of snowfall when Chawton House was her family’s home.

"I have such strong memories of Chawton in the snow, it was so exciting! My father, Jeremy Knight (Edward Austen’s 3rd great grandson) was always first up in the morning so was usually the first to know. “You might want to look out of the window”, he would say around my bedroom door soon after sunrise. I excitedly climbed down the ladder from the mezzanine in my bedroom, where I slept, and ran through our kitchen (originally the billiard room), along the oak panelled hall and into our sitting room (originally the grand dining room of Chawton House). From the window seat I could see across the front of the house, the bottom of the lawns, the church and the front paddocks and nothing thrilled me more than looking out over a thick covering of snow. The thicker the better - if the snow was deep enough, we would be cut off for the first day – Dad couldn’t get to work and local schools would be closed.

Dad would spend the morning around the house and grounds clearing drains, checking pipes and spreading grain in the woods to help the estate pheasants and wildlife survive.

Dad (Jeremy Knight) looking over the lawns, with Flash, Granny's Labrador. Photo © Caroline Jane Knight

Walking through the woods spreading grain with Dad's Labrador, Candy, and Flash. Photo © Caroline Jane Knight

The gates to the hidden walled garden at the top of the lawns. Photo © Caroline Jane Knight

But in the afternoon, the long, wide lawns to the southwest provided the perfect gradient and safe landing for a toboggan, tray or even an empty feed bag. I loved the rush of wind on my face as my father and I hurtled down the lawn, but as I didn’t want to crash into the bushes at the bottom, I often leapt off the back of the toboggan before we reached them. It was impossible not to be in fits of giggles as I rolled in the soft snow.

Dad hurtling down the lawns on a toboggan. Photo © Caroline Jane Knight

One year we had close family friends, Jake and Amber, staying for Christmas before departing for a skiing holiday. They had their own boots and skis and had great fun, with my older brother Paul, skiing right from the rose garden at the top of the lawns, all the way down to the yew trees on the edge of the church yard. There was no ski lift, of course, and it was a long walk back up to the top, but no one minded at all! I was too young, my feet far too small for the ski boots, and Dad tobogganed so I could join in the fun.

After an hour or two Dad would walk around the house and grounds once more, no doubt worried about how the roof and pipes would bear up when the snow thawed. Maintaining the old manor, with extremely limited funds, was a constant challenge for my father but I was not burdened with such things and thought of the snow as nothing but wonderful.

Our neighbours, Andrew and Jonathan, would often come and join in the fun and we would build a snowman, complete with stones for eyes, a twig for a nose and a woolly hat and scarf.

With neighbours Andrew and Jonathan building a snowman (that's me on the right) Photo © Caroline Jane Knight

Happy days.

Caroline Jane Knight

© Caroline Jane Knight

Credit: Chawton House in the snow article header photo courtesy chawtonhouselibraryreadinggroup.blogspot

Caroline is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SCROLL DOWN TO SUBSCRIBE TO AUSTEN HERITAGE

Chawton House - so much more than a library

Caroline Jane Knight, Jane Austen's fifth great niece, rejoices in the restoration of the name Chawton House and shares some of the delights of her ancestral home.

Chawton House Library have announced a change of name for the Knight family ancestral home, once owned by Jane Austen's brother Edward (my fourth great grandfather).

“Having previously been known as Chawton House Library due to our significant collection of early women’s writing, we are shortening our name to Chawton House. Our amazing library collection will still be at the core of what we do but we have had lots of feedback to say that potential visitors to the house and grounds are confused by having ‘library’ in our name, which could mean we are only open to library users, when we want everyone to be able to come and enjoy the house, the gardens, the tearoom and – of course – the treasure trove which is our library collection”

Chawton House was built around 1585 by John Knight, the first squire featured in the heraldry windows on the first-floor picture gallery, and has been passed down through sixteen generations. The freehold of my childhood home has never been sold, and is now owned by my uncle, Richard Knight.

Chawton House (picture courtesy chawtonhouse.org)

Great aunt Jane Austen herself called her brother Edward’s house ‘Chawton Great House’, or ‘the Great House’ and I have seen postcards from the Victorian era which name the house ‘Chawton Manor House’.

In Montagu George Knight (the thirteenth squire) and William Austen Leigh’s book Chawton Manor and It’s Owners about the history of the estate, the house and the twelve generations of owners that had come before Montagu, the house is referred to as Chawton House throughout, including in text copied from old documents in the family archive. When I was a child, we called our home Chawton House and what a delight it is to see the name of the house restored.

Chawton Manor and It's Owners - A Family History, published in 1911

What has never been in doubt is the beauty of the Chawton estate and the house itself. As Montagu said:

“The beauty of the situation, the venerable age of the Manor House, the old-world character of the village, and its literary associations; the fact that the property (though it has been owned by members of several families) has only once since the Norman Conquest changed hands by way of sale and purchase—all these advantages give the place a peculiar title to be considered as a specimen south English manor.”

The house sits at the end of the village halfway up a hill, with the garden and grounds reaching up further still behind the house. The straight gravel drive leads down from the road to Chawton Church, St Nicholas, on the right and the stables on the left, before going up the hill to the front entrance. The natural dip in the landscape around the house had once provided a moat and later a ha-ha—or dry moat—a recessed fence that provided boundaries but did not obscure the view.

The front entrance is approached from the west by five stone steps up to a large archway, above which carved stone heraldry proudly declares this the home of the Knights. The carving depicts a shield, or coat of arms, with a lozenge design running diagonally down from left to right and the motto Suivant Saint Pierre (Follow St Peter) in bold letters below. The arms are topped with a knight’s helmet and the family crest: a sixteenth-century monk named The Greyfriar. If you visit the house, see if you can find The Greyfriar hidden in the panelling on the first floor - you'll have to look carefully to find it.

The Greyfriar hidden in the panelling at Chawton House

The house itself has been subject to continuous change, with additions, renovations and alterations ever since it was built—a four-storey extension to the north wing added in the Victorian era had been the last major works (since removed and with it my childhood bedroom). The result is a labyrinth of staircases, passages and rooms. The dark interior and numerous interconnecting doors only add to the confusion. The layout is complicated, and it is difficult to describe—it’s a wonderful house to explore.

Fanny Knight, Edward Austen Knight’s eldest daughter and one of Jane’s favourite nieces, wrote to her old governess Miss Chapman in 1807 describing the Great House:

This is a fine large old house, built long before Queen Elizabeth I believe, & here are such a number of old irregular passages &c &c that it is very entertaining to explore them, & often when I think myself miles away from one part of the house I find a passage or entrance close to it, & I don’t know when I shall be quite mistress of all the intricate, & different ways.

Beautiful gardens and woodlands sweep up behind the house and at the top of the lawns you will find the walled garden, which as a child felt like a ‘secret garden’ known only to the family and our closest friends.

The gates to the 'secret' walled garden (photo courtesy of chawtonhouse.org)

I hope you get a chance to visit Chawton House. The collection of early women’s writing is wonderful, but the house, gardens and family history are a delight for any visitor.

Caroline

For more information about Chawton House and to plan your visit, click here.

Header image courtesy of chawtonhouse.org.

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SUBSCRIBE BELOW TO AUSTEN HERITAGE

Janeites revive a lost Christmas tradition of Jane Austen’s family

Janeites revive an old Christmas tradition of Jane Austen's Chawton family

Sir Richard Knight’s reclining statue had been in the back of the church for 300 years, so great-aunt Jane Austen would have known him as well as I did. I lived at Chawton House until I was 18 and every year on Christmas Eve I took the short walk half way down the front drive to Chawton Church to see Sir Richard and check he had his holly. This family tradition was lost when my family left Chawton but, thanks to the wonderful Janeite community, has now been revived.

I liked the stillness of the quiet church when I was a girl, and I loved to read the inscriptions and plaques dedicated to the Knights and the Austens—records of the centuries of our ancestors in Chawton.

Chawton Church

At the very back of the church, on the right wall of the chancel, Sir Richard Knight reclined in marble. He had been installed three centuries earlier on what appeared to be the mantelpiece of a grand fireplace. He wore battle dress and a wig like the judge. The marble behind Sir Richard was carved in relief with suits of armour, swords and helmets. The monument was finished at the top with the Knight coat of arms, crest and motto. The date ‘1679’ marked his death and was all I could make out from the Latin inscription below the mantel. The Knight arms were featured in the stained-glass window next to Sir Richard on the back wall of the chancel.

The Knight arms (on the left) - diagonal lozenges with a flower - in stained glass in Chawton church

With too many ‘greats’ for me to calculate—about ten, I thought—I had decided to consider myself Sir Richard’s great-granddaughter. A more accurate description of the relationship between us, with the house having passed to numerous different branches of the family, seemed difficult to determine and unnecessary. He was a Knight from Chawton, Edward Austen had become a Knight from Chawton and so was I; therefore, we were family and all of the previous Squires were my great-grandfathers—simple.

Sir Richard had a serious face, and I tried to imagine what sort of man he had been. The faces of our many ancestors were depicted in oil paintings throughout the house, but this was the only three-dimensional statue. It was as if he were frozen in time, lost in the eyes of Medusa, his white marble skin smooth and flawless. He looked well fed and healthy.

Sir Richard Knight (1639 - 1679) reclines in Chawton Church

When he left provisions in his will for the monument to be constructed, did he think that three hundred years later, his descendants would still be living in Chawton House? Sir Richard could not possibly have imagined that this estate would one day boast a world-renowned writer as one of its own. And especially not a woman! Jane would have known Sir Richard just as I did; much of the old wooden church had been destroyed by fire and rebuilt in 1872, but the chancel and family vault underneath had remained intact, and Sir Richard had not been disturbed.

In 1644, when Sir Richard was five, Oliver Cromwell enforced an Act of Parliament which banned Christmas celebrations in England, as Christmas was considered a wasteful festival that threatened core Christian beliefs. The ban was not lifted until Sir Richard was twenty-one, although many people had continued to celebrate Christmas in secret. I hated the thought of Sir Richard missing Christmas as a child and hoped his family had marked the occasion, even if behind closed doors.

It was a family tradition to place a sprig of holly in the hand of his statue in December every year—to ensure Sir Richard didn’t miss out on any more Christmases. We were forced to give up Chawton House as our family home at the end of the 1980s and, during this very difficult time in my family’s history, our traditions were forgotten – including Sir Richard.

That was until 16th December 2015 when Rita L Watts (the woman behind the popular Facebook page All Things Jane Austen) visited Chawton with author Cassandra Grafton for Jane Austen’s birthday. I awoke the next morning (in Melbourne where I now live) to photographs of Sir Richard with holly in his hand! My heart sang and I jumped for joy – it meant so much to me that Sir Richard didn’t miss Christmas.

Rita L Watts putting holly in Sir Richard's hand

Every year since, a Janeite has volunteered to visit Sir Richard for me and this tradition has been reinstated. This year I was contacted by Zoe Wheddon from the Basingstoke area, who had a trip to Chawton planned. Zoe had read the story of Sir Richard and his Christmas holly in my book and wanted to make sure he had his holly this year.

Zoe Wheddon continues the tradition

Helped by the wonderful garden manager at Chawton House, Andrew, Zoe cut some holly from the woods, just as we would have done, and put it in Sir Richard's hand.

Thank you Zoe - I can truly enjoy Christmas now, knowing that Sir Richard is enjoying it too!

Caroline

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SUBSCRIBE BELOW TO AUSTEN HERITAGE

Win an exclusive gift box of Jane Austen goodies

Win an exclusive box of Jane Austen goodies from Jane's family.

To celebrate the launch of the audiobook of Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage, read by award-winning narrator, Alison Larkin, you can WIN Jane Austen and Chawton goodies in an international giveaway.

Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage is the story of Caroline Jane Knight, Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last descendant of the Austen family to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. Caroline explored the same places around Chawton House and its grounds as Jane did, dined at the same dining table in the same dining room, read in the same library and shared the same dream of independence.

To enter the competition, simply order or download your copy of the audiobook of Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage direct from ALISON LARKIN PRESENTS before 22nd December 2017, and you will automatically be entered into the draw.

NOTE: Only purchases direct from Alison Larkin Presents will be entered into the draw.

FIRST PRIZE: Austen Heritage Gift Box from Caroline Jane Knight

1. JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE - A hardcover copy of Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage, by Caroline Jane Knight (Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen descendant to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote), personally dedicated to the winner and signed by Caroline.

2. A PRIVATE VIDEO CHAT WITH CAROLINE JANE KNIGHT - In a private video chat at a mutually convenient time, we can talk about my fifth-great aunt Jane Austen, growing up in Chawton, writing Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage, or anything else you would like to know.

3. DOWNLOAD THE COMPLETE WORKS OF JANE AUSTEN AUDIOBOOKS by award-winning narrator, comedienne and author, Alison Larkin. Alison's Complete Works of Jane Austen includes the Audiofile Earphones Award-Winning Sense & Sensibility - "Alison Larkin’s narration will captivate listeners from the first sentence." Audiofile enthused, "This version stands out as one of the best.". Alison is my favourite audiobook narrator and I was thrilled when she agreed to narrate the audiobook of Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage.

4. THE KNIGHT FAMILY COOKBOOK - A facsimile copy of The Knight Family Cookbook (c. 1793), only available at Chawton House. Jane's brother Edward (my fourth great grandfather) was adopted by the Knight's to inherit Chawton. Jane lived in Chawton Cottage, a short walk from Chawton House, for the last eight years of her life, from 1809 to 1817.

A facsimile copy of The Knight Family Cookbook

5. JANE AUSTEN, EDWARD KNIGHT AND CHAWTON: COMMUNITY AND COMMERCE By Linda Slothouber - One of my favourite books about Chawton. Linda visited Chawton a couple of years ago and researched in my family archives to build a picture of Chawton in Jane's time and how her brother Edward (my fourth great grandfather) managed the estate. A fascinating and unique insight into the village that Jane Austen lived in.

6. DVD COPY OF PRIDE & PREJUDICE: HAVING A BALL - Watch an authentic reenactment of the Netherfield Ball by the BBC in 2013, filmed in the Great Hall of Chawton House. The last family event to be held 'at home in the Great Hall' was my 18th birthday in 1988.

Pride & Prejudice: Having a Ball filmed in the Great Hall at Chawton House

The Great Hall set for my 18th birthday dinner August 1988

7. L'OCCITANE EN PROVENCE PACK - Pamper yourself with Ultra Rich Body Lotion, Lip Balm, Toner and Hand Cream, from luxury French beauty label L'Occitane En Provence. Nothing to do with Jane Austen, I just love L'Occitane!

8. CHRISTIANA CUP & SAUCER, EARL GREY TEA - Enjoy a cup of earl grey tea from the English Tea Shop in a tea cup from Australian designer Christian (I am in Melbourne at the moment and have the same cup and saucer myself)

9. LEATHER BOUND NOTE BOOK - Beautifully leather bound, like the books I remember from our family library in Chawton, for you to scribble down your inspirations.

SECOND PRIZE: Austen Heritage Gift Set

1. JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE - A hardcover copy of Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage, by Caroline Jane Knight (the last Austen descendant to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote), personally dedicated to the winner and signed by Caroline.

2. DOWNLOAD THE COMPLETE WORKS OF JANE AUSTEN AUDIOBOOKS by award-winning narrator, comedienne and author, Alison Larkin. Alison's Complete Works of Jane Austen includes the Audiofile Earphones Award-Winning Sense & Sensibility - "Alison Larkin’s narration will captivate listeners from the first sentence." Audiofile enthused, "This version stands out as one of the best."

3. DVD COPY OF PRIDE & PREJUDICE: HAVING A BALL - Watch an authentic reenactment of the Netherfield Ball by the BBC in 2013, filmed in the Great Hall of Chawton House. The last family event to be held 'at home in the Great Hall' was my 18th birthday in 1988.

THIRD PRIZE: Austen Heritage Gift Bag

1. JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE - A paperback copy of Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage, by Caroline Jane Knight (the last Austen descendant to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote), personally dedicated to the winner and signed by Caroline.

2. DOWNLOAD AN ALISON LARKIN AUDIOBOOK OF YOUR CHOICE - You might choose the Audiofile Earphones Award-Winning Sense & Sensibility - "Alison Larkin’s narration will captivate listeners from the first sentence." Audiofile enthused, "This version stands out as one of the best.". Or perhaps Pride & Prejudice with Songs from Regency England - the choice is yours.

The audiobook of Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage will be officially launched at a Facebook Live Jane Austen Birthday Tea event on 16th December at 3pm EST at the Austen Heritage Facebook page. For more details of this special event, hosted by Caroline Jane Knight and Alison Larkin, click HERE.

To enter the competition, don't forget to buy your copy of the audiobook of Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage direct from Alison Larkin Presents:

Winners will be drawn live on Facebook at Austen Heritage @CarolineJaneKnight on 23rd December at 3pm EST, and informed by email.

Good luck!

Caroline

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SUBSCRIBE BELOW TO AUSTEN HERITAGE

Jane Austen and the Prince - Part 2

Jane Austen skillfully resists an extraordinary attempt by the palace to influence her writing.

On 13th November 1815 Jane Austen visited the Prince Regent’s London palace. In later correspondence the Prince's librarian, Reverend Clarke, suggested Jane Austen dedicate Emma to the Prince – a man she disliked. But this wasn’t the only unwelcome suggestion he made to Jane!

Despite writing anonymously Jane must have known she was a success – not many writers caught the attention of the Prince Regent, or received a personal invitation to view the royal library at Carlton House. After the visit, Jane continued a correspondence with Reverend Clarke, the Prince’s librarian, which lead to a couple of extraordinary suggestions. First, it was suggested that Jane dedicate Emma to the Prince Regent – a man she disliked – to which she eventually agreed. You can read about that here.

Jane duly forwarded a copy of Emma for inclusion in the Prince’s library and must have thought that would be the end of it. But, the royal ‘suggestions’ didn’t end there. In March, 1816, Mr Clarke wrote:

Pavilion: March 27, 1816

Dear Miss Austen, - I have to return to you the thanks of His Royal Highness, the Prince Regent, for the handsome copy you sent him of your last excellent novel. Pray, dear Madam, soon write again and again. Lord St. Helens and many of the nobility, who have been staying here, paid you the just tribute of their praise.

The Prince Regent has just left us for London; and having been pleased to appoint me Chaplain and Private English Secretary to the Prince of Cobourg, I remain here with His Serene Highness and a select party until the marriage. Perhaps when you again appear in print you may chuse to dedicate your volumes to Prince Leopold: any historical romance, illustrative of the history of the august House of Cobourg, would just now be very interesting.

Believe me at all times,

Dear Miss Austen,

Your obliged friend,

J. S. Clarke.

How wonderful that Jane’s writing was so well liked by the nobility, she was urged to write more. But how awkward for Jane! She has already conceded to the dedication of Emma to the Prince – an association that was not to her liking – and now they wanted to interfere with the content of her writing.

Jane faced a tricky situation. She needed to put an end to all attempts of influence from the palace, firmly and without ambiguity, but without causing offence or being disrespectful. Jane writes the most wonderful dialogue for her characters in awkward circumstances, it is fascinating to see how she dealt with such a tricky situation in her own life.

Jane responded:

My dear Sir, - I am honoured by the Prince’s thanks and very much obliged to yourself for the kind manner in which you mention the work. I have also to acknowledge a former letter forwarded to me from Hans Place. I assure you I felt very grateful for the friendly tenor of it, and hope my silence will have been considered, as it was truly meant, to proceed only from an unwillingness to tax your time with idle thanks. Under every existing circumstance which your own talent and literary labours have placed you in, or the favour of the Regent bestowed, you have my best wishes. Your recent appointments I hope are a step to something still better. In my opinion, the service of a court can hardly be too well pail, for immense must be the sacrifice of time and feeling required by it.

You are very, very kind in your hints as to the sort of composition which might recommend me at present, & I am fully sensible that an historical romance, founded on the House of Saxe Cobourg might be much more to the purpose of profit or popularity, than such pictures of domestic life in country villages as I deal in, but I could no more write a romance than an epic poem. I could not sit seriously down to write a serious romance under any other motive than to save my life, and if it were indispensable for me to keep it up and never relax into laughing at myself or other people, I am sure I should be hung before I had finished the first Chapter. No, I must keep to my own style and go on in my own way; and though I may never succeed again in that, I am convinced that I should totally fail in any other.

I remain, my dear Sir,

Your very much obliged, and sincere friend,

J. Austen.

Chawton, near Alton, April 1 1816

Jane starts with a suitable tone of thanks and deference to the Prince and Mr Clarke. It is hard not to note, with amusement, Jane’s explanation for not responding to early letter – perhaps she had made previous attempts to end the correspondence but the palace wouldn’t take the hint!

In her second paragraph, with wit and an air of self-deprecation (a polite veneer to suggest the weakness in being able to take up his suggestion is hers, rather than his for making such a suggestion in the first place!), Jane firmly stands her ground.

I have always loved this story – and have always been inspired by what is, to me, the finest example from Jane's private letters of her strength, self-determination, diplomacy and skillful use of language.

Caroline

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SUBSCRIBE TO CAROLINE'S JOURNAL BELOW

Jane Austen and the Prince - Part 1

Jane Austen's agonising dilemma following a visit to the Prince's London mansion

Shortly after my seventeenth birthday Blackadder III, set in the Regency era when Jane had been in Chawton, was screening on television and was very popular. I was still living in Chawton House with my family (it was three weeks before my grandfather died and our lives changed forever, but I didn't know that at the time). I was excited and impressed when my father told me about Jane's dedication of Emma to the Prince Regent. But I was also a little confused—why had Jane dedicated one of her precious works to such a foppish idiot as played by Hugh Laurie?

Jane had not liked the Prince at all and wrote candidly to Martha Lloyd on 16 February 1813 in support of the Prince’s estranged wife, Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel:

I suppose all the World is sitting in Judgement upon the Princess of Wales’s Letter. Poor woman, I shall support her as long as I can, because she is a Woman, & because I hate her Husband—but I can hardly forgive her for calling herself “attached & affectionate” to a Man whom she must detest—& the intimacy said to subsist between her & Lady Oxford is bad—I do not know what to do about it;—but if I must give up the Princess, I am resolved at least always to think that she would have been respectable, if the Prince had behaved only tolerably by her at first—.

But the Prince Regent was a fan of Jane’s, and a couple of years later, she was invited to view the library at Carlton House, his London residence. It was early October 1815, as Emma was being prepared for publication, and Jane travelled to London to stay with her brother, Henry, in Hans Place. Henry fell ill, and Dr Baillie, who just happened to be the Prince Regent’s physician, was called in. Dr Baillie mentioned to Jane that the Prince was a great admirer of her works and that he had a set of them in each of his lodgings and read them often. Dr Baillie had therefore thought it right to inform His Royal Highness that Miss Austen was staying in London, and the Prince had instructed Reverend Clarke, the librarian of Carlton House, to show her the library.

Carlton House, separated from Pall Mall by a 'screen'. Image : Ackerman's Repository, 1811

The invitation was accepted, and Jane visited Carlton House on 13th November 1815. I was in awe—to think of Jane going to the Prince’s mansion.

Carlton House Library. Image: janeausteninvermont.blog)

While she was there, Reverend Clarke said he had been asked to convey that if Miss Austen had any other novel forthcoming, she was at liberty to dedicate it to the Prince. What a tricky position Jane must have been in! How could she possibly associate her work with a man she thought so little of? But, on the other hand, how could she refuse such as invitation from royalty. Jane must have agonised over the decision as two days later, she wrote to Reverend Clarke to ask to what extent she was obliged to comply:

SIR,—I must take the liberty of asking you a question. Among the many flattering attentions which I received from you at Carlton House on Monday last was the information of my being at liberty to dedicate any future work to His Royal Highness the Prince Regent, without the necessity of any solicitation on my part. Such, at least, I believed to be your words; but as I am very anxious to be quite certain of what was intended, I entreat you to have the goodness to inform me how such a permission is to be understood, and whether it is incumbent on me to show my sense of the honour by inscribing the work now in the press to His Royal Highness; I should be equally concerned to appear either presumptuous or ungrateful. (Nov 15th 2015)

Reverend Clarke responded the very next day:

DEAR MADAM,—It is certainly not incumbent on you to dedicate your work now in the press to His Royal Highness; but if you wish to do the Regent that honour either now or at any future period I am happy to send you that permission, which need not require any more trouble or solicitation on your part.

Jane eventually decided to be diplomatic and dedicate Emma to the Prince Regent, adding a ‘perfectly proper’ dedication:

Jane Austen's dedication of Emma to the Prince Regent

Her exaggerated deference would have no doubt pleased the Prince but also revealed her true feelings to those who knew her.

But, this was not the last awkward suggestion made by Reverend Clarke to Jane. More of that next week in Part 2 of Jane Austen and the Prince.

Caroline

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SUBSCRIBE TO CAROLINE'S JOURNAL BELOW

Why Jane Austen self-published her first novel

Jane Austen's fifth great-niece talks about the challenges Jane faced in publishing her first novel.

This week we have marked the anniversary of the date Jane Austen first became a published author – 30th October 1811. It is easy to assume that a writer as gifted as Jane would not have too many difficulties in publishing her works. But, after two failed attempts, Jane decided the only way to guarantee publication was to take the financial risk herself and pay to be published.

From an early age, Jane wanted to be a published author. She was a prolific writer as a teenager short stories, poems, satires and plays (collectively called her Juvenilia) and it is believed that in 1795, when Jane was twenty years old, she wrote Elinor and Marianne, an epistolary novel in the form of letters from one character to another, the first incarnation of Sense and Sensibility. Like so many ‘facts’ about Jane, this is an assumption based on the available evidence and is subject to conjecture. Unlike Pride & Prejudice (also written originally as an epistolary novel) where the main characters are often apart, the Dashwood sisters are usually together and I find it hard to see how the story would allow for a steady stream of letters.

Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, as portrayed by Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet.

She began writing her second epistolary novel in 1796 and a year later had a finished work she titled First Impressions. On 1st November 1797 Jane’s father approached publisher Thomas Cadell with the manuscript of First Impressions but was ignored. That was probably a blessing, as the maturity and skill Jane brought to the revisions of her earlier manuscripts led to the Pride and Prejudice that has been cherished by readers and academics for two centuries, but Jane would not have known that at the time.

In 1803, George Austen sold the copyright of Susan, Jane’s first complete narrative work for £10 to Benjamin Crosby. I can only imagine how thrilled Jane would have been and I have no doubt the family would have waited in anticipation of its release. But Crosby failed to keep his word and didn’t publish Susan. Six years later in desperation, Jane wrote to Mr Crosby under the pseudonym Mrs Ashley Dennis—M.A.D. for short. She implored him to publish the novel, or she would have no alternative but to seek publication elsewhere:

Wednesday 5 April 1809 68(D). To B. Crosby &.. Co.

Gentlemen

In the Spring of the year 1803 a MS. Novel in 2 vol. entitled Susan was sold to you by a Gentleman of the name of Seymour, 1 & the purchase money £10. reed at the same time. Six years have since passed, & this work of which I avow myself the Authoress, has never to the best of my knowledge, appeared in print, tho’ an early publication was stipulated for at the time of Sale. I can only account for such an extraordinary circumstance by supposing the MS by some carelessness to have been lost; & if that was the case, am willing to supply You with another Copy if you are disposed to avail Yourselves of it, & will engage for no farther delay when it comes into Your hands. — It will not be in my power from particular circumstances to command this Copy before the Month of August, but then, if you accept my proposal, you may depend on receiving it. Be so good as to send me a Line in answer, as soon as possible, as my stay in this place will not exceed a few days. Should no notice be taken of this Address, I shall feel myself at liberty to secure the publication of my work, by applying elsewhere. I am Gentlemen &c &c

MAD–

After only two days, she received a quick response:

Direct to Mrs Ashton Dennis Post office, Southampton

[Messrs. Crosbie [sic] & Co., Stationers’ Hall Court London]

Madam

We have to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 5th inst.

It is true that at the time mentioned we purchased of Mr Seymour a MS. novel entitled Susan and paid him for it the sum of 10£ for which we have his stamped receipt as a full consideration, but there was not any time stipulated for its publication, neither are we bound to publish it, Should you or anyone else [sic] we shall take proceedings to stop the sale. The MS. shall be yours for the same as we paid for it.

London Ap 81809

~ Dennis Post Office Southampton.

For B. Crosby & Co I am yours etc.

Richard Crosby

Photo of ms autograph copy of Crosby’s letter (Photo: reveriesunderthesignofausten.wordpress.com)

I could only imagine how frustrated Jane must have been. Jane could have decided not to subject herself to such disappointment and to give up, but she didn’t.

When Jane moved to Chawton in July 1809, her writing had all but stopped (following the death of her father and subsequent home insecurity). Within a month of her arrival, she started writing again, and less that eighteen months later Sense & Sensibility was ready for publication. Despite her limited funds, Jane paid for Sense and Sensibility to be published on commission, which guaranteed that her book would be printed and available for sale – as close to 'self-publishing' as you could get in Jane’s time. The words at the bottom of the title page state 'PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR'. Jane would share in the profits from any sales of the book but also carry the financial risk if it didn’t sell. Jane backed herself and made a profit of £140 (the equivalent of about £5,000 today)—no doubt a welcome boost to the Austen ladies’ modest income.

Sense & Sensibility was a success and Jane Austen never paid to publish her work again.

And Susan? The family bought back the manuscript from Crosby after Jane died (without revealing it was by the same author as novels such as Pride & Prejudice), for the ten pounds he originally paid, and published Jane's first complete narrative work as Northanger Abbey. How fitting it is that Jane now appears on the ten pound note, but what a shame she didn't know that Susan was eventually published.

Caroline

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SUBSCRIBE TO CAROLINE'S JOURNAL BELOW

The Heraldic Stained-Glass Windows at Jane Austen’s Great House

The heraldic windows at Jane Austen's Great House hide an extraordinary family history of adoptions and succession

Chawton Great House, as Jane Austen called her brother's home, was built around 1585 by John Knight, and has passed down from one generation to the next ever since – the freehold has never been sold. The heraldic stained glass-windows in the picture gallery serve as a wonderful record of centuries of continuous Knight family ownership, but hide an extraordinary family history.

Chawton House Library posted a wonderful picture of Edward Austen's heraldic window this week, and it reminded me when I was about 12 and, for the first time, I learned the names of every squire that had come before my grandfather Edward Knight III, the fifteenth squire.

It was 1982, and my father and I stood at the heraldic windows on the landing outside my grandparents’ bedroom chambers on the first floor of Chawton House. We lived in the north wing, but moved around the house freely (except for a couple of apartments that were rented out). Dad explained the significance of the two sets of windows which overlooked the inner courtyard - each depicted six shields in stained glass that recorded each member of our family who had owned Chawton House, in succession. Under each vibrantly coloured shield were the names of the squires with their arms and the date of their inheritance of the house.

The first set of heraldic windows at Chawton House

Multiple squires were listed underneath a few of the shields in the stained-glass windows, but most shields listed only one squire. Although each shield was a different combination of arms—evidence of families joining through marriage, inheritance and adoption—every shield included gold lozenges set diagonally on a green background (the Knight arms). Some of the squires were of particular note and familiar to me, but other names I knew little about. From the first to the last, each was named Knight.

Long before I first saw the stained-glass windows, I had seen in my grandparents’ quarters an iron fireback marked ‘JK 1588’—the name and date under the first glass shield was ‘John 1583’. John Knight was the principal builder of the house. I was about seven when I first calculated that my family had owned Chawton for nearly four centuries—it was such a long time, it might as well have been forever. I later discovered that the Knights had been in Chawton for over six and a half centuries and had held land in the parish since at least 1307.

Chawton House today (photo courtesy www.chawtonhouse.org)

I had long assumed I was a direct descendant of John Knight, but was soon to learn that it wasn’t quite that simple.

The stained-glass windows made it easy for me to establish just how many squires there had been. ‘John 1583’, ‘Stephen 1620’, ‘John 1627’, ‘Richard 1636’ and ‘Sir Richard 1641’ completed the names under the first three shields. Sir Richard left no children and chose another Richard—Richard Martin, his aunt’s grandson, as his successor on the condition that he took the name of Knight. (The name ‘Richard’ was obviously of some amusement to Jane. At the beginning of Northanger Abbey, Jane tells us that Catherine Morland’s father was ‘a very respectable man, though his name was Richard.’)

‘Richard 1679’ and ‘Christopher 1687’ were under the next shield, which included a quarter of arms with three birds (at least that’s what they looked like to me). Both Martin brothers were also childless, making three childless squires in succession. ‘Who decides who the next squire will be?’ I asked, and my father explained that it was the duty of each squire to name their heir, usually their eldest son. If the squire had no children, then a suitable relation had to be found to continue the family legacy and be prepared for the responsibilities he would inherit. In an unusual move for the time, Christopher left the estates to his sister, Elizabeth, who ran the estates well. I was thrilled to hear a woman had run the estates but was confused as I had always believed only men could inherit - you can read more about that in my book Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage, and what Jane might of thought of the extraordinary terms of Elizabeth's will that changed the course of history, led to legal challenges of Edward Austen's ownership of the estates and caused uncertainty for Jane and her Chawton home.

The second set of windows started with Thomas Knight, second cousin to George Austen who appointed George the Rector of Steventon, a parish also owned by the Knights. Like all previous shields, Thomas’s shield included the Knight arms of gold lozenges set diagonally on a green background but with the addition of a small flower towards the bottom left.

Second set of heraldic windows at Chawton House

Like her brothers, Elizabeth had no children and chose as her successor her second cousin Thomas from the Brodnax branch of her family. Thomas was also heir to Godmersham Park, and his succession brought the estates together under the same squire. Thomas had already received his inheritance from the May family and, as a condition, had changed his name to Thomas May by an Act of Parliament, as was required. When he sought another Act of Parliament to change his name once more—to Knight, to inherit Chawton House—it was flippantly suggested in the House of Commons that a law be passed to allow Thomas to call himself whatever he liked. ‘Or whatever he May,’ my father quipped. The arms were altered to signify the distance of the blood relationship between Elizabeth and Thomas. ‘Thomas 1737’ and ‘Thomas 1781’ were the names under the next two shields.

Thomas left the estates to his son, Thomas II, who was childless and who, at the end of the eighteenth century, chose Jane’s older brother, Edward Austen, my fourth great-grandfather, as his heir. He was commonly referred to as Edward Austen Knight, despite never having carried both surnames, and Edward’s heraldry included both the Knight and Austen arms. The Austen arms, a red chevron with three black bear paws, came from the John Austen Esq. of Broadford in Kent, a picturesque Elizabethan residence. Over the fireplace in the entrance hall at Broadford are the Austen arms, with the date ’1587’— the Austens had equally as long a history as the Knights.

Edward (Austen) Knight's heraldic shield at Chawton House

The windows were installed by Montagu, the thirteenth squire. Montagu and Florence had not had children, and for the eighth time in our history, the squire did not have an heir. Montagu chose his brother’s first-born son, Lionel, my great grandfather (and Edward Austen’s great grandson), to succeed him.

My mind burst with all the twists and turns of the inheritance of the house over the centuries. The Chawton estate passing from father to eldest son was said to be tradition, but our history showed this not to be the case for the majority of the squires. Since John Knight—the first squire in the stained-glass windows—the house had been passed from father to eldest son on only five occasions, the last being from Lionel to Edward (my grandfather), the fifteenth squire, in 1932.

My grandfather died in 1987 and Chawton was inherited by my his eldest son (my uncle), Richard Knight. I was seventeen and Chawton House could no longer be kept as our family home. Although Chawton House is now on a long lease to a charity, Richard has retained the freehold to be passed down to his descendants, and I would like to think that one day the heraldic windows will be updated with the next generation of owners, each carrying the name of Knight.

Caroline

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SUBSCRIBE TO CAROLINE'S JOURNAL BELOW

Jane Austen's books missing from her family's library

Jane Austen's fifth great niece solves the mystery of why Jane's novels were missing from the family library

I spent hours as a child searching for Jane Austen’s books in my family’s ancestral library at Chawton House. A collection of three thousands books put together over four centuries lined the walls of the library, but none of them were Jane’s. Why didn’t Jane’s own family (my family) consider her worthy of inclusion in the collection?

When I was a girl, the Knight collection of books inherited by Edward Austen (who was adopted by the Knight’s to become the 11th Squire of Chawton) was in the library at Chawton House, the room my grandparents (Edward Knight III – Edward Austen’s great great grandson and the 15th Squire of Chawton – and Elizabeth) used as a sitting room. I visited the library every day and would sometimes take a book off a shelf and peak inside. The spines cracked as I levered open the hard leather covers. Some of the books were highly decorated with elaborate gold leaf designs.

Many of them were complete with a bookplate inside the front cover, indicating which of my ancestors had been their original owner. I was fascinated by each ancestor’s choice of bookplate design—and books—because I considered their choices an indication of personality. Edward Austen Knight’s bookplate, for example, was much plainer than Thomas Knight’s:

Thomas Knight (9th Squire of Chawton) bookplate

Edward Austen Knight (11th Squire of Chawton) bookplate

Unlike the rest of the family, who appeared to have satisfied themselves with one bookplate design, Montagu (Edward Austen Knight’s grandson) had three—and each was elaborate and bold. I particularly liked Montagu’s round design; it was the only circular bookplate I had seen. In a seemingly typical example of Montagu's personality (he was one of my more flamboyant ancestors), his bookplate was in many of books, including those already in the collection when he inherited it!

Montagu Knight (13th Squire of Chawton) bookplates

I particularly liked the books with beautifully hand-painted illustrations of flora and fauna from around the world and would marvel at the pictures – bright and clear as the day they were painted. I couldn’t help but run my fingers over the thick pages. Most of the books were extremely old, and many were in languages I didn’t understand. Tales of foreign travel; illustrated natural histories, books of letters, volumes of poetry, novels, and books on politics, law, sport, history, estate management, art, and religion were interspersed with estate records, family history and our Chawton heritage.

The library was very much a male domain (which was hard to ignore), despite the fact that a woman—Jane—was the celebrated and much-revered literary member of our family. The bookplates showed that the collection had been largely put together by the men of the family, and most of the books had been written by men. The journals of foreign travels were of gentlemen’s journeys—photographs and illustrations focused on men’s achievements and interests, not women’s. Jane would have known the older books, either at Chawton or in the library in Godmersham Park before they were moved to Chawton. I could imagine her browsing through the eclectic mix of books, perhaps to gain knowledge and inspiration for her writing and I wondered which books had been Jane’s favourites.

Was Jane, the most talented writer in the family, resentful of the lack of female representation in the library? Was she offended that her novels weren't included? I can't deny being privately outraged, on her behalf, although I never had the courage to mention it!

Northanger Abbey first edition in the lower reading room at Chawton House (photo courtesy of Chawton House Library)

Perhaps she expressed her views through the voice of Anne Elliot in Persuasion, in a lively conversation with Captain Harville. But you can read more about that in my book - I want to talk about something else in this article.

Many years later I discovered that four of Jane’s books were listed in the Godmersham Park library catalogue of 1818, the year after she died. At the very end of the catalogue, in a small section labelled ‘Drawing Room’, the novels published in Jane’s lifetime were listed: Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814) and Emma (1816). They were recorded as having been printed in London, as sitting on shelf six and as comprising three volumes each. My father told me that Jane's novels would, of course, been immediately added to the family collections - it is likely a set was also held in the Chawton as well. Much of the Godmersham collection was moved to Chawton when Godmersham was sold in 1874, so there should have been multiple early copies of Jane’s novels.

But by this time I had realised the extent of the crippling financial pressures faced by my family that had resulted in the sale of most of our property, assets and valuable possessions in the first half of the 20th century – which is why valuable eighteenth century editions of Jane’s books weren’t in our family library (there were modern version on my parent’s bookshelves in our north-wing quarters). Jane's books weren't sold due to any lack of respect or love for Jane and her extraordinary talents, but as a desperate act by a family in financial crisis.

It was hard not to feel a little sad at all of the books that had been lost from our family collection since Jane’s time. But, in February of this year, something wonderful happened. A set of Jane’s novels from 1833, complete with Montagu’s bookplate, was discovered in Texas. It was an important first edition of a set of Austen novels by Bentley, who, for the first time, had published Jane’s novels as a ‘complete works’. The owner, Sandra Clark, who had been collecting Austen editions for years, had generously sent them back to Chawton House – and I whooped for joy. At least one of our family’s copies of Jane’s books, which I had searched for in the library when I was a child, had returned home.

The first edition set of Jane Austen's novels, generously returned to Chawton House

And now, in even more exciting news, the Godmersham Lost Sheep Society in the USA have launched a campaign to locate other books, now held in collections around the world, that came from Edward Austen Knight’s libraries. I would like to sincerely thank Deb Barnum from JASNA in Vermont and everyone else who is involved. How wonderful that other books from our family library might be found, I can't tell you how much this means to me.

So, take a look at the old books on your bookshelves - could any of them be from the library that Jane Austen knew so well?

And how do you know if your books are from Chawton? Montagu Knight’s bookplate, of course!

For more information about the project click here

Caroline

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SUBSCRIBE TO CAROLINE'S JOURNAL BELOW

The generous act Jane Austen did not approve of

Caroline Jane Knight discusses why Jane Austen was not impressed when Edward was given control of the Knight estates

Rather than making Edward Austen wait until she died, his adopted mother, Catherine Knight, stood aside to allow Edward to manage the estates he would eventually inherit. This was reported to be a generous act, but Jane did not agree!

When Thomas Knight II died in 1794, he left his estates to his wife, Catherine, for her life and confirmed Edward Austen to be the eleventh squire of Chawton. But four years later, Catherine passed over the estates to Edward to run, rather than have to wait for her death:

"Catherine Knight out of her love and affection for Edward Austen and in order to advance him to their present possession of the estates which were settled on him and his issue in remainder under the will agreed to convey all the estates unto and to the use of Edward Austen during the joint lives of him and her Catherine Knight subject to a rent charge or clear annual sum of £2,000 clear of all deductions and taxes to be reserved and made passable."

To many this may have seemed to be a great gift to Edward – after all he would have an income of about £15,000 a year (according to estimates) – but the burden and responsibility of managing the estates had also passed to Edward as well as the risk of the income falling short.

Jane did not hide her views on Catherine’s actions. On 8 January 1799, she wrote to Cassandra:

Mrs. Knight giving up the Godmersham Estate to Edward was no such prodigious act of Generosity after all it seems, for she has reserved herself an income out of it still;—this ought to be known, that her conduct may not be over-rated.—I rather think Edward shews the most Magnanimity of the two, in accepting her Resignation with such Incumbrances.

Edward made Godmersham his primary residence and made annual visits to Chawton for up to five months at a time. Most of Edward’s income from his Hampshire estates came from land rental and payments related to use of the land. He let houses, farms, mills and labourers’ cottages. Rent provided a steady income, which Edward supplemented by working in the woodlands.

The Chawton lands of Thomas Knight - (photo copyright Caroline Jane Knight)

In the excellent book Jane Austen, Edward Knight & Chawton, Commerce and Community, Linda Slothouber reports (after studying my family's archives in Chawton) that wood was routinely cut from the 9,000 acres at Chawton, and Edward sold firewood, hop poles—cut from slender branches to support growing hops—and fencing rods harvested through coppicing—that is, cutting wood from a tree without killing it. Trees were cut down or topped and the timber sold, and bark was sold to one of the several tanneries in Alton. After Catherine died, Edward as able to rely most heavily on the coppices that supplied underwood, the most renewable resources - income from timber had been up to ten times higher in her lifetime, perhaps to pay her annual stipend.

Edward’s annual income of £15,000 may sound like a lot (half as much again as Mr Darcy’s £10,000), but there were many financial demands to be met. Between a quarter and a half of Edward’s gross earnings were spent annually on expenses, including labour, repairs, professional fees, tithes, transport, taxes and rates.

Edward Austen Knight

Edward was fastidious. He kept bank clerks on their toes, correcting mistakes in their ledgers, and he took swift and firm action to collect money where he was owed. He met with his steward annually and inspected the accounts in detail. ‘He must have been more his own “man of business” than is usual with people of large property, for I think it always was his greatest interest to attend to his estates,’ Caroline Austen (his niece) recalled. However, despite careful management of his financial affairs, in 1811 Edward decided to sell the Abbots Barton (another Hampshire estate) after thirteen years of stewardship. Through the sale, Edward was able to cut running costs by selling land that was expensive and difficult to maintain and to release capital to finance expenses. It was the responsibility of the landed gentry to preserve the family's land and fortunes for future generations, so the significance of selling land must not be underestimated.

Catherine Knight received £2,000 a year for thirteen years until her death in 1812, which was equivalent to nearly sixty per cent of the net profits of his Hampshire estates. Perhaps Jane had been right; the early passing of the estates to Edward by Catherine was not such an act of generosity after all.

Caroline

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SUBSCRIBE TO CAROLINE'S JOURNAL BELOW

Why I wrote 'Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage'

Caroline Jane Knight reveals why, after 25 years of silence, she has written about her unique childhood in the heart of Jane Austen's literary home.

I have spent most of my adult life trying to forget Chawton and avoiding all reminders of my heritage, my famous ancestor and Chawton House, which I miss so dearly but which can never again be my family home. I never thought I would end up writing a book about it.

I lived at Chawton House from birth, with my parents, brother and extended family. Jane Austen’s House Museum (the cottage where Jane revised, wrote and published her most famous novels) was only a short walk away and brought thousands of visitors a year to Chawton, and from as young as I can remember I was super-proud of my fifth great-aunt and what she had achieved – she was a phenomenal role model to grow up with.

Jane Austen's House Museum in the village of Chawton. Photo copyright: J.B.Grantham

My early life was filled with the delights of living in a sixteenth-century English manor cocooned in centuries of my Austen and Knight family heritage, the good cheer of family gatherings and Christmas traditions in the Great Hall of Chawton House, the beauty of a country life, and the joys of helping her Granny bake cakes and serve Jane Austen devotees in the tea room in the Great Hall at the front of the house. The family fortune had run out decades before I was born, but that made no difference to my sense of connection to Chawton, and Jane Austen, and naive hope that Chawton Great House (as Jane had called it) would forever be my family's home.

But, in 1987, when I was seventeen, my grandfather, Edward Knight III (the fifteenth squire of Chawton and Edward Austen’s great great grandson) died, leaving a depleted estate in financial ruin. After four centuries and fifteen generations of continuous family ownership, we had no choice but to leave Chawton House, Jane Austen and our heritage behind. I was heartbroken when my parents, brother and I left in 1988.

Chawton House in 1987, when I lived there with my family. Photo copyright Caroline Jane Knight.

Since 2003, Chawton House has been open to the public as Chawton House Library, the Centre for Early Women’s Writing 1600 – 1830. It has become a world renowned and respected centre of learning and has been visited by scholars and Janeites from all over the world.

Twenty five years after we left and I had learned not to think about Chawton or Jane Austen at all. It didn’t hurt if I didn’t think about it, so I simply avoided all reminders and never spoke about my family, heritage or connection to the world famous author. My career had taken me to Australia in 2008, to become the CEO of a big marketing agency, and I was so busy, I didn’t have time to think about anything else.

But in 2013, my life was turned upside down. The widely celebrated bicentennial of the publishing of Pride and Prejudice was impossible to avoid – even on the other side of the world – and started a chain of events in my life that would take me back to my roots and reunite me with my ‘very great’ great-aunt, Jane Austen. It was difficult at first, for the loss of Chawton still weighed heavy on my heart.

Pride & Prejudice first edition. Photo copyright BBC

In Melbourne, where I now live, I talked to a group of women at the local Jane Austen Society and a packed crowd at a National Trust event, and I was astounded by the level of interest in me, and in my family. Jane Austen fans wanted to know every detail of my connection with the world-famous author and my life at Chawton—from the family library, rooms, furniture and crockery in Chawton House to the local walks and family traditions I shared with Jane. Historians were interested in my memories of the last years of Chawton House as a family home.

I quickly realised the philanthropic opportunity that existed for the Jane Austen community to support literacy, and started the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation in 2014, to increase literacy rates in communities in literacy crisis.

During a short visit home that same year, I spent a day in Chawton with Simon Langton (the director of BBC TV 1995 Series of Pride & Prejudice staring Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle). We spent hours walking around the house and grounds talking about my childhood in the heart of Jane Austen’s literary home and legacy. Simon was particularly curious about my relationship with my grandfather (who never spoke to me) and of the sense of responsibility—and perhaps of a need to ‘keep up appearances’—that drove my grandparents to continue to host community events despite being in financial crisis. He was also interested in how Jane’s fame had brought a continuous flow of tourists to our home and family. ‘It’s a fascinating story,’ he said and suggested I write a book.

I had never had any ambition of becoming an author – Jane Austen had set the bar so high in my family and I knew I hadn’t inherited her phenomenal literary talents. But, I realised that I am a source of primary knowledge. I have a unique first-hand experience of a period in the history of our family and the Chawton estate. Many writers and historians have documented the history of Chawton House and the Austen and Knight families, but little is known about the last decades of Chawton House as my family’s home. The demise of my family’s ancestral estate is typical of the demise of many English country manors and with stories such as Jane's and series such as Downton Abbey, it is easy to imagine ancestral homes in their heyday.

Netherfield Ball in BBC TV 1995 Series Pride & Prejudice

It is, perhaps, not so easy to understand the reality of the burden when the money has run out, the enormous challenges that are faced and the effect this has on the families.

Montagu Knight, the thirteenth squire of Chawton, was the last family member to write a book about the house and its owners, and that book was published more than one hundred years ago. My parents had a copy of Chawton Manor and It’s Owners- A Family History (written by Montagu and William Austen Leigh, published in 1911) which I read during my stay in England. I had not seen the book for years and savoured every world. It was a fine record of the Knight family since they first owned property in Chawton in 1307, and the various branches that had owned Chawton House, including his (and my) branch, the Austens. But I wished he had told me more about himself and his life in Chawton. It gave me no clues as to his personal experience or thoughts.

By the end of my visit, I felt compelled to finish off the story Montague had started. I cherished the records my ancestors had left for me, and I wanted to do the same for future generations. But, as well as the facts, I also wanted to share what I thought and how I felt about it all. Jane’s rise to global stardom had made it impossible for me to avoid reminders of what I missed so dearly and I knew that writing a book would be cathartic and help heal my heart.

Writing about Chawton has been the hardest (I have never written before) and most emotional (I cried for the first eighteen months of writing) undertaking I have ever attempted. But, it has also been the best thing I have ever done. I have shared some of my first hand experience, left a record for future generations and turned my biggest source of pain into my biggest source of joy. I am so grateful to have grown up at Chawton House and for the support of my family in writing this book. I am enormously privileged to be able to call Jane Austen my fifth great-aunt and to have shared Chawton with her.

Caroline

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers. 15% of any profits made are donated to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

SCROLL DOWN TO SUBSCRIBE TO CAROLINE'S JOURNAL

Chawton House - the historic home of the Austen Knight family

Caroline Jane Knight shares the history of Jane Austen's Great House

Chawton House was built around 1585 by John Knight and has been passed down through sixteen generations, from different branches of the Knight family (the last being the Austen branch), never being sold.

Chawton House was my childhood home – I lived there until I was eighteen. I am the granddaughter of the fifteenth squire, Edward Knight III, the third great grandson of Edward Austen Knight, Jane Austen’s brother. Jane spent the last eight years of her life living in Chawton Cottage, just 400 metres from the ‘Great House’ as she called the Elizabethan manor her brother had inherited from the Knights (wealthy cousins). I shared the details of how and why Edward became heir to the Knight estates, property and fortune in last week’s journal entry - you can read it HERE.

Now I want to tell you more about the history of Chawton House.

The Knight family had held land in the parish of Chawton since 1307. The Knights are prominent in the earliest Court Rolls which have been preserved, and by 1524 William Knight had a lease on the site of the manor (there was a previous wooden structure of which little is known) and the farm of Chawton. The lease was renewed to John Knight the younger and in 1551 he bought the land. John’s son Nicholas bought the Advowson rights in 1578 (the right to recommend a member of the Anglican clergy for a vacant benefice, or to make such an appointment) and the Knights were in full possession of Chawton. Nicholas’s son John took on the major task of building a new manor house and became the first squire of the Chawton House we know today.

Since the house was built in the mid-1580s (the major build would have taken a couple of years), it has been subject to continuous change with additions, renovations and alterations. John Knight (1563 – 1621), the original and principal builder, continued to expand the manor throughout his life.

The probable plan of the original build from Chawton Manor and It's Owners - A Family History. You can see the entrance to Chawton House on the right, and the north wing on the left.

The entrance porch tower and front of the house were heightened with a brick parapet and the main line of the building extended to the west to add a buttery, or service room, and the Oak Room above. John then added the south wing, which housed the library and a new main staircase, and a kitchen wing to the east. The new eastern and southern wings were connected with a servant’s passage at the rear of the Great Hall on the ground floor and the picture gallery behind the bedroom chambers on the first floor.

From the same book as above. The house was doubled in size and significantly extended to the rear.

I was told by my family that the date 1655 carved on a wainscot on an internal door is evidence of considerable alterations made in the middle of the seventeenth century. The addition of a four storey extension the north wing added in the Victorian era had been the last major addition to the house (this has since been removed). Over the centuries the house had also been subject to a continuous stream of minor alterations with the changing needs and tastes of each Squire. The result was a labyrinth of staircases, passages and rooms. The dark interior and numerous interconnecting doors only added to the confusion. The layout was complicated, and it is difficult to describe—visitors frequently got lost.

The Tapestry Gallery, where four staircases and six doors meet - it's easy to get lost!

Jane moved to Chawton in 1809. Fanny Knight, Edward’s eldest daughter and one of Jane’s favourite nieces, wrote to her old governess Miss Chapman in 1807 describing the Great House:

"This is a fine large old house, built long before Queen Elizabeth I believe, & here are such a number of old irregular passages &c &c that it is very entertaining to explore them, & often when I think myself miles away from one part of the house I find a passage or entrance close to it, & I don’t know when I shall be quite mistress of all the intricate, & different ways."

During the English Civil War (1642 – 1651) many other manor houses in the area, such as Basing House, were destroyed by Oliver Cromwell’s army, the ‘Roundheads’. Chawton House was saved, through an extraordinary stroke of luck (you can read more about that in my book) and, due to its age and wonderful position, was considered a particularly desirable property. Montagu Knight (1844 – 1914) was certainly very proud of Chawton, and in his book Chawton Manor and It’s Owners – A Family History (written with William Austen Leigh, published in 1911) proclaims:

"The beauty of the situation, the venerable age of the Manor House, the old-world character of the village, and its literary associations; the fact that the property (though it has been owned by members of several family [branches]) has only once since the Norman Conquest changed hands by way of sale and purchase—all these advantages give the place a peculiar title to be considered as a specimen south English manor."

Chawton House was the home of the Knight family until 1988 (I am the last member of the family to grow up there). I was seventeen when my grandfather died (Edward Knight III, great great grandson of Edward Austen), leaving a depleted estate in financial ruin and a house in need of restoration. The following year we left Chawton. My uncle Richard Knight (my grandfather’s eldest son) has retained the freehold of Chawton House to be passed down to his eldest son, honouring the century old traditions of our family. But, it is now on a long lease to a charity, has been beautifully restored and is open to the public as Chawton House Library. One day Chawton House might once again be the private home of the Knight family, but for now it is open to the public and I highly recommend a visit to my family's historic home.

Caroline

Caroline Jane Knight is Jane Austen's fifth great-niece and the last Austen to grow up at Chawton House on the ancestral estate where Jane herself lived and wrote. You can read more about Caroline's extraordinary childhood in JANE & ME: MY AUSTEN HERITAGE, available in PAPERBACK, HARDBACK, E-BOOK and AUDIOBOOK at all good online retailers.

SCROLL DOWN TO SUBSCRIBE TO THE AUSTEN HERITAGE JOURNAL

The adoption that changed Jane Austen's life, and mine.

When Jane was eight, her brother Edward was adopted. Little did she know how significant this would be for her writing career.